Everybody knows that the best memories come when our plans veer off-script. We'll always remember that night when we stumbled into some unmarked restaurant we'd never heard of and laughed with new friends we'd just met, more than dining at the cafe carefully selected from the guidebook for its perfect ambience and view. Endearingly, the Georgians I've spent time with seem to rely on serendipities. They're part of the plan: we'll go, and somehow, everything will work. Relying on the kindness of strangers may not have worked out so well for Blanche duBois, but I'm starting to sense that Georgia couldn't exist without it.

This weekend, when I joined a friend and his NGO colleagues on an outing to the countryside for hiking and barbecue, things seemed pretty planned out. A marshrutka (that's the mini-bus) had been arranged to take us to the countryside in search of the ruins of two 11-century castle fortresses on twin peaks. (Incidentally, driving here is really something. Imagine a windswept beach, inland a bit from the flat shoreline, where there are high dunes and valleys, smaller rises and deep grooves. Now imagine that these have hardened into a crust. Now generously spread a final layer of loose, fist-sized stones over the tableau, and you have some idea of Georgian roads. A kidney massage, is how my boss generously described the experience of traveling on them. The trick is to make sure your marshrutka has a high roof, or you’ll end up with a concussion by day’s end.)

We drove until we arrived at the village at the base of the hills that were said to hide these ruins. We stopped among the villagers for a protacted discussion on directions. I wondered what they offered. Turn left at the seventeenth field of corn? After the pomegranate trees, veer right? You can't miss it? Negotiations seemed to conclude and we poured back into the marshrutka, but this time, I noticed with three local teenagers crowding the front seats.

I turned to look questioningly at Epo, our leader. She smiled broadly, "This is how it is in Georgia! These guys, you know, they just stand around the village wondering what to do with their day. So we come by and they say they will show us how to get to the fortresses. Why not? Something interesting for them, maybe."

The boys led us up a steep hill, the marshrutka spinning wheels and spitting out rocks and we bumped our way along until the road abruptly stopped in a farmer's yard. The rest of the way, we'd have to hoof it.

Here's the next thing I learned: if you ask a Georgian if it's far, and they say no, then that translates into a 4 hour roundtrip hike off any discernible path, up nearly vertical rock climbs then down on your rear careening into a gorge on a vertical slide, then up again, down again. Because none of was expecting this kind of thing, nobody had packed any water. Our stomachs were completely empty. And I? Was in flip-flops.

I am also a huge weenie, and so was nearly delirious with thirst and sore, dragging my limbs as I watched these insane Georgian kids

sprinting up rock inclines so that they could attach themselves barnacle-like to the walls and then haul us up by hand.

Finally, parched and crazy, we reached these fortress ruins, sticking up into the sky, nothing as far as we could see that would differ the landscape from how it looked when Tamerlane came to conquer it. One fortress was named "Mother's Castle," the other, laughably, "Inaccessible." It was some hell of high ground, I can tell you. Davy Crockett and the Alamo boys would have had a different tale to tell if they had this piece of real estate to defend. I can also say that we never, never would have found this place without these village boys. If you hire a tourist agency to take you on climbs, it will cost you about $200 per person. These boys refused to accept any money. "We don't do this for money" they replied scornfully before two of the three scampered off to other obligations.

The third, we took him with us for the barbecue. Another serendipity. "Where shall we go to eat?" I asked. Everyone shrugged. We'll see. We drove only five more minutes before stopping by the edge of a stunning lake, a lake that would be packed with weekend picnickers at home, but which was completely alone for us. While the men prepared the pork for grilling, we raced down to the lake where the Georgian women jumped in, clothes and all, laughter and splashing.

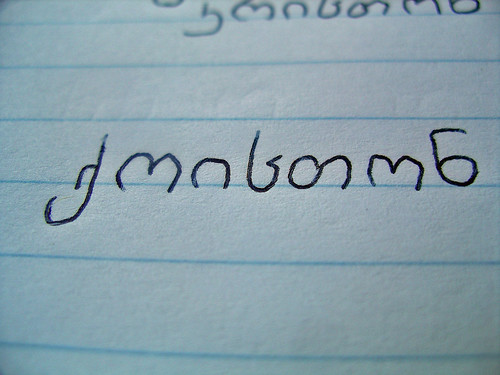

When dinner was ready, we couldn't find our little guide. He'd gone off to hide while we ate. He refused to come join us, claiming, no, no, really, he wasn't hungry at all. He'd not eaten a thing all day. Epo told him that she was about to make a toast to him, and perhaps the only thing worse than accepting some sort of payment for your services is refusing a toast in your honor. He came. When he wasn't looking, a fully prepared plate was shoved in his lap and he laughed. He tried to ignore it but eventually ate it up. Later that night, when we dropped him back off at his village, Anton tried to give him the bag bursting with leftover food so he could take it to his mother and 5 brothers and sisters. He tried to run away in the street rather than accept, but Anton grabbed his arm and yanked him back. He squirmed and thrashed and broke free, all the while yelling "no, no, no!" and so Anton dropped the bag of food in the road and said he would leave it for the dogs. The boy took it. I am sorry if we embarrassed him, but I am sure his mother will be happy to have it. That's him pictured in the post below, by the way, sitting by the lake.

As we drove back to Tbilisi in darkness, the women all started singing the songs they know, in that lovely 3-part harmony that every Georgian seems to know how to do. What is it about this place? After the USSR imploded, Georgia had the most sudden and precipitous economic collapse, a bloody civil war, a complete meltdown of infrastructure and supply that left the economy so crippled, it remains one of the very poorest countries in Europe. But somehow, there is so much joy everywhere, something of a different breed completely from what I've experienced in any other former Soviet republic. Spontaneous song, always, grown professional women laughing like little girls and jumping headlong into a just-discovered lake. I don't mean to paint a simplistic picture, and certainly people are as quick to anger as they are to laughter, and the black-jacketed toughs of Tbilisi surl with the best of them on street corners. People complain endlessly about the hopelessness of their government and their screwed-up society. Everything is a mess, and everybody knows it. Nobody can find work, crime is rampant, and hard drug use is epidemic among young men. But there's somehow a sort of defiant optimism in private life. I asked some Georgians about this. Why, basically, aren't you like the Russians? Some said that despite everything, their quality of life is still somehow better: they have fresh fruits and vegetables, they have good water and beautiful nature. I think just as important, they also have these ties to each other, that didn't break down when everything else did. They can rely on a strange village kid to spend his entire day showing them around; he can rely on a van full of strangers to feed his family that week. No Georgian would ever worry too much about getting stranded somewhere unfamiliar (unless it was wild Svaneti): just knock on a door, ask for some food, this is Georgia! Can you even guess how many times a Georgian, without rolling eyes or placing tongue-in-cheek, has quoted to me what their 12th century poet Shota Rustaveli said: that which we give makes us richer; that which we keep is lost. I mean, sure, we all

say this kind of rot when we want to think of ourselves nobly, or we cynically doubt the motives of anyone spouting such nonsense, and one intellectual Georgian went so far as to ponder whether this aphorism

described Georgians at the time or somehow

created a subsequent cult of Georgian hospitality, but, can you imagine, nobody has winked that it's all a bit of sound and fury.

And yes, I hear myself. I've spent enough time snorting at wild-eyed naivete to know it when I spot it. And I am trying, I really am, to avoid being taken in by people's myths about themselves. But it's not easy to maintain your steely resolve and clinical detachment in the face of so much generosity of spirit.

Generosity of spirit. DC is going to

eat me for lunch when I come back.